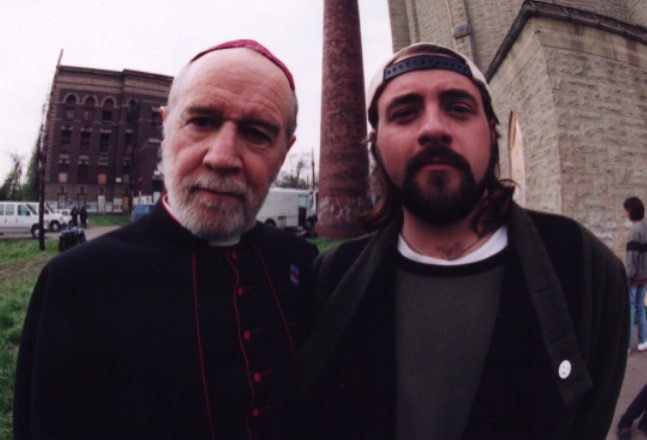

Carlinite Fun: The comedian with director Kevin Smith on the set of 'Dogma'

By Kevin Smith | Special Guest Columnist

They say you should never meet your heroes. I've found this a good rule to live by, but as with any rule, there's always an exception.

My first exposure to George Carlin was in 1982, when HBO aired his "Carlin at Carnegie" stand-up special. When I saw the advert-featuring a clip of Carlin talking about the clichéd criminal warning of

"Don't try anything funny," and then adding, "When they're not looking, I like to go ...," followed by a brief explosion of goofy expressions and pantomime-I immediately asked my parents if I could tape it on our new BetaMax video recorder.

That was a hilarious bit. But when I finally watched the special, Carlin blew my doors off. Whether he was spinning a yarn about Tippy, his farting dog, or analyzing the contents of his fridge, Carlin expressed himself not only humorously, but amazingly eloquently as well. I was, as they say, in stitches.

And that was before he got to the Seven Words You Can't Say on Television.

I was 12 years old, watching a man many years my senior curse a blue streak while exposing the hypocrisy of a medium (and a society) that couldn't deal with the public usage of terms they probably employed regularly in their private lives. And while he seemed to revel in being a rebel, here was a man who also clearly loved the English language, warts and all-even the so-called "bad words" (although, as George would say, there are no such things as "bad words"). I wouldn't say George Carlin taught me obscenities, but I would definitely say he taught me that the casual use of obscenities wasn't reserved just for drunken sailors, as the old chestnut goes; even intelligent people were allowed to incorporate them into their everyday conversations (because George was nothing if not intelligent).

From that moment forward, I was an instant Carlin disciple. I bought every album, watched every HBO special, and even sat through "The Prince of Tides" just because he played a small role in the film. I spent years turning friends on to the Cult of Carlin, the World According to George, and even made pilgrimages to see him perform live (the first occasion being a gig at Farleigh Dickinson University in 1988). Carlin influenced my speech and my writing. Carlin replaced Catholicism as my religion.

Sixteen years later, I sat across from the star of "Carlin at Carnegie" in the dining room of the Four Seasons Hotel in Los Angeles. It was a meeting I'd dreamed of and dreaded simultaneously. George Carlin was the type of social observer/critic I most wanted to emulate ... but he was a celebrity, too. What if he turned out to be a true prick?

What I quickly discovered was that, in real life, George was, well, George. Far from a self-obsessed jerk, he was mild-mannered enough to be my Dad. He was as interested as he was interesting, well-read and polite to a fault-all while casually dropping F-bombs. But most impressive, he didn't treat me like an audience member, eschewing actual conversation, electing instead to simply perform the whole meeting, more "on" than real. He talked to me like one of my friends would talk to me: familiar, unguarded, authentic.

I made three films with George over the course of the next six years, starting with "Dogma" and his portrayal of Cardinal Glick, the pontiff-publicist responsible for the Catholic Church's recall of the standard crucifix in favor of the more congenial, bubbly "Buddy Christ." A few years later, I wrote him a lead role in "Jersey Girl"-as Bart Trinke (or "Pop"), the father of Ben Affleck's character. It called for a more dramatic performance than George was used to giving, but the man pulled it off happily and beautifully. (Something most folks probably don't know about George: He took acting very seriously. The man was almost a Method actor.) Sadly, I consider that "Jersey Girl" part my one failing on George's behalf, and not for the reasons most would assume (the movie was not reviewed kindly, to say the least). No, I failed because George had asked me to write a different role for him.

In 2001, George did me a solid when he accepted the part of the orally fixated hitchhiker who knew exactly how to get a ride in "Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back." When he wrapped his scene in that flick, I thanked him for making the time, and he said, "Just do me a favor: Write me my dream role one day." When I inquired what that'd be, he offered, "I wanna play a priest who strangles children."

It was a classic Carlin thing to say: a little naughty and a lot honest. I always figured there'd be time to give George what he asked for. Unfortunately, he left too soon.

He was, and will likely remain, the smartest person I've ever met. But really, he was much more than just a person. Without a hint of hyperbole, I can say he was a god, a god who cussed.